|

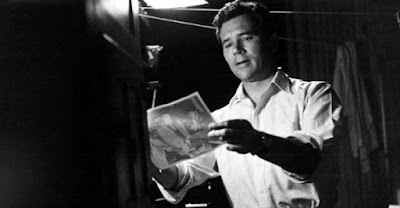

| Kirk Douglas, Robert Arthur, 'Ace in the Hole' (1951). |

By Paul Parcellin

Gossip, Lurid Facts, Scandal Keep the Tabloid Presses Rolling

This article contains spoilers, so you may want to see these films before reading any further.

When we see a disheveled, groggy Richard Conte breaking into his own office in the middle of the night, desperate to record a story on the company’s Dictaphone machine, you know you’re watching noir. The scene could be set in almost any kind of office but it feels most at home in the newsroom — it works in an insurance company, too, but that’s a different movie (“Double Indemnity”).

In the first half of the last century newspapers had an undeniable excitement and mystique about them that has faded in more recent times. Back then they were a perfect breeding ground for the darkest of noir tales.

Picture a dingy roomful of men in their shirt sleeves and fedoras, furiously clattering out hot stories on Royal typewriters and editors marking them up with number 2 pencils. A cloud of Chesterfield smoke lingers in the air. City streets are awash in newsprint, subway strap hangers’ hands are smudged with black ink and news hawkers bark out the day’s biggest headlines.

Part of the reason that newspaper journalism of yore, especially tabloids, fit perfectly with the film noir perspective is their focus on crime, scandal and salacious gossip. With big, garish headlines they often told tales of bullets fired, shell casings recovered and blood spilled. But apart from the pulpy stories they printed, the newspaper game was a grimy business — literally. Ink, newsprint and hot lead type were the materials that went into making that hunk of paper that landed on your doorstep each morning or the tabloid you snatched up at a news stand near your bus stop.

These days, with computer imaging and typography, print journalism, such as it still exists, has grown a good deal more antiseptic. Old school newsrooms, Linotype machines and photo darkrooms have dissipated into the ether along with the cigarette smoke. But in their glory days they were part of the rough, gritty stuff that noir is made of. Yet, beneath the surface of these newspaper films lies a deep seated fear of media demagoguery, its potential to deliver propaganda to the masses and the unchecked power it could potentially wield — fears that have stayed with us to this day.

|

| Howard Duff, 'Shakedown' (1950). |

Most of those in the journalism game were and are straight shooters, but noir by its very nature focuses on humanity’s dark side, and the journalists of film noir are nothing if not amoral and shamelessly power hungry. We see that in "Shakedown" (1950). Cutthroat photographer Jack Early (Howard Duff) has a seemingly uncanny ability to take sensational pictures of breaking news events. Early is evasive about how he manages to be at the right place where dramatic events unfold. It turns out he’s getting tips from racketeer Nick Palmer, who lets him know about crimes, usually involving henchmen the crime boss want to get rid of, before they happen. For Early, the tips are a bonanza that pave the way to a job on the city’s newspaper. But as his career advances he develops a taste for double crosses, himself, setting up a crime boss for an assassination. He plans to stand on the sidelines and capture it all on film. Eventually, Early is killed, but the camera he has stationed on a tripod takes pictures of the shooter in the act of rubbing him out. It’s a fitting last act for a crime photographer who liked to catch all of the lurid details on film.

|

| Richard Conte, Bruce Bennett, 'The Big Tip Off' (1955). |

In "The Big Tip Off" (1955), Richard Conte plays two-bit newspaper columnist Johnny Denton who gains notoriety by printing red-hot information on upcoming gangland activities. Like Jack Early, he is getting his information from a shadowy associate of his old buddy, Bob Gilmore (Bruce Bennett) . Unbeknownst to Denton, Gilmore is running a charity scam. Although the information he’s receiving offers him an opportunity to boost his faltering career, Denton soon has misgivings. In voice-over he reflects on his first encounter with mob brutality. “I didn’t think of the ethics of it until it was too late,” he mutters. “A human life ended in violence.” Soon others begin questioning his seemingly prescient reporting, but he claims immunity from revealing his sources. But in time it becomes clear that he’s more concerned with self enrichment than with protecting a news source’s identity.

When the film’s action sags toward the middle a mood-lifting charity telethon with musical guests is staged with Denton as the master of ceremonies. But telethon organizer Gilmore has a plan of his own. He’s set to abscond with the telethon proceeds and will frame Denton for murdering his erstwhile accomplice.

|

| Kirk Douglas, Porter Hall, 'Ace in the Hole' (1951). |

Like Denton, opportunistic newshound Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas) puts his career goals ahead of moral principles — and he has few of those. In "Ace in the Hole" (1951), Tatum knows he’s got a big fish on his line when an Indian relics hunter Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict) gets trapped in a cliff dwelling cave-in. Tatum will do anything to keep the story active. He and Sheriff Gus Kretzer (Ray Teal), who has agreed to grant Tatum exclusive contact with Leo, browbeat the construction contractor into using a more time-consuming rescue strategy. Meanwhile, after Tate’s news dispatches hit the streets droves of gawkers appear on the scene, and before long a traveling carnival sets up — a literal media circus. Almost everyone stands to gain something from Leo’s predicament. Leo’s wife, Lorraine (Jan Sterling), was ready to leave him but decides to stick around when she realizes there might be a buck to be made from the ordeal. Sheriff Kretzer is dancing to Tatum’s tune because the reporter has promised him favorable press for his reelection campaign. But in the end, all does not go well for Leo, and when the din of carnival barkers recedes into the New Mexico desert he is all but forgotten.

|

| Tony Curtis, Burt Lancaster, 'Sweet Smell of Success' (1957). |

Like Tatum, syndicated newspaper columnist J. J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) In "Sweet Smell of Success" (1957) is one in a long line of unethical journalists who manipulate events and people to maintain an outsized influence on public opinion. Lancaster’s Hunsecker is an unabashed egomaniacal monster who surrounds himself with show business figures, politicians, underlings and other useful idiots. One of his entourage is small-time press agent Sydney Falco (Tony Curtis), who relies heavily on the columnist to push the propaganda he writes for his meager list of clients. Meanwhile, Hunsecker is obsessed with breaking up his sister Susan’s (Susan Harrison) relationship with jazz guitarist Steve Dallas (Martin Milner) — we can only speculate about Hunsecker’s deeper motives. He demands that Sydney drive a wedge between the young couple and declares a moratorium on publishing any of his publicity blurbs until he gets the job done. Sydney dutifully takes on the job of ruining Dallas’s reputation, and in doing so deceives and cajoles a cigarette girl into doing a sexual favor for another columnist who agrees to publish a slur against the young guitarist. His gambit works, for a while, at least, but as soon as Sydney begins to believe he’s on top of the world the rug is yanked out from under him. Although Hunsecker’s plot backfires, we can assume he’ll continue to disseminate venom for many years to come, as will others of his ilk.

|

| Clifton Webb, Dana Andrews, 'Laura' (1944). |

Another news columnist and broadcaster, Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb), is the monster in "Laura" (1944). He’s filthy rich, earning an unheard of 50 cents per word for his literate dispatches that are printed in hundreds of papers around the country. As the story opens in Waldo’s self-described “lavish” apartment, Det. Lt. Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) interviews him as he investigates the murder of advertising executive Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney). Both Waldo and playboy Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price) knew the late young beauty and are therefor murder suspects. We see in flashback the genesis of Waldo’s relationship with Laura, which blossoms into a strictly platonic friendship. Waldo acts as her mentor, teaching her how to dress and behave in upper crust society. He aims to mold her into a decorative, cultured ornament, much like the museum pieces housed in glass cases in his living room. Carpenter, however, is enamored with her and has proposed marriage, earning himself Waldo’s scorn, but Carpenter seems immune to Waldo’s attempts to poison the relationship. In flashback we see Waldo disposing of another would-be suitor by ridiculing him in his column — after reading Waldo’s poisonous article, Laura is no longer able to take the would-be beau seriously.

As the investigation proceeds we learn that Laura was killed by a shotgun blast to the face at her apartment’s doorway, which adds the tantalizing possibility that the victim may not be who everyone has assume it is, a possibility that proves true when Laura makes a most unexpected reappearance. But before she reemerges McPherson begins to fall in love with a portrait of her hanging over the mantlepiece. “Laura” is in part a romance in which McPherson and the heroine come to share a mutual attraction. But the concluding scene focuses on the shotgun murder weapon and a grandfather clock. Waldo loaned the clock to Laura — the shotgun is his own.

|

| Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, 'The Big Clock' (1948). |

While scribes such as Waldo are most frequently the bad guys of newspaper noir, they aren’t the only villains of journalistic corruption. Sometimes a publisher can be the heavy. In "The Big Clock" (1948) we meet media mogul Earl Janoth (Charles Laughton), who keeps his charges on a tight leash. He’s the kind of executive who fires the janitor who left the supply closet light on overnight. One of Janoth’s employees, Crimeways magazine editor George Stroud (Ray Milland), is in the doghouse with his neglected wife, Georgette (Maureen O’Sullivan). George gets an adrenaline junkie’s thrill out of chasing down high-profile murder cases and is conflicted by his recent decision to chuck his fast-paced city life and move to the placid countryside, all in the name of maintaining marital bliss. It’s a sure bet from the start that a hot story is going to hook George and his move to the country will be put on hold.

That comes to pass when Janoth’s former mistress, Pauline York (Rita Johnson), tells the publisher that she has fresh dirt on him. She’s been blackmailing him — he pays for her “singing lessons.” But now she’s ready to squeeze him for a larger payout. It’s only a short while after making her pronouncement that she is dead at Janoth’s hands. In an effort to throw the police off his trail, Janoth orders George to investigate the case and find the man whom he glimpsed but did not recognize just outside Pauline’s apartment — it was George, and that’s another sticky matter. As the police pursue blind leads, the Crimeways investigation picks up steam and the atmosphere becomes downright surreal. The magazine’s staff has unheard of investigative authority in an open criminal investigation while the police stand sheepishly on the sidelines. It’s apparent that Janoth’s company holds excessive, some might say fascistic, power over law enforcement authorities. In the end it’s George, not the police, who crack the case. But it’s not until he discovers how constrictive, mechanized and demoralizing an environment the company is that he is able to free himself from it and move back to the country and a less tumultuous way of life.

|

| Rosemary DeCamp, Broderick Crawford, 'Scandal Sheet' (1952). |

Newspaper editor Mark Chapman (Broderick Crawford), is another journalist who probably should have taken up residence on a quiet country lane, but instead he remains in the big city where his past has come back to haunt him. In "Scandal Sheet" (1952), Chapman finds it hard to keep a lid on a tragic incident that makes him look guilty of murder. His estranged wife, Charlotte (Rosemary De Camp), comes calling at a lonely hearts dance organized by Chapman’s paper, the Express. She threatens to publicly disclose information about his past that could ruin him — years ago he abandoned her and changed his identity. They have a verbal dust up that turns into a scuffle and she’s accidentally killed. Chapman works out a cover up, making it look like she slipped in the tub and the police believe his story. But it’s challenging to keep things under wraps when the paper’s ace crime reporter, Steve McCleary (John Derek), keeps digging up facts that hit a little too close to home. Unfortunately for Chapman, he has overseen the transformation of his once respectable paper into a muck-raking gossip rag. The kind of mud puddle he’s just stepped into — executive slays wife he abandoned — is just the stuff that papers like his gobble up. McLeary and his colleague Julie Allison (Donna Reed) are dogged in their pursuit of the culprit whom the paper has dubbed the Lonely Hearts Killer. Clearly, Chapman’s in over his head, but he will stop at nothing to scuttle the investigation. That includes committing murder when a reporter stumbles on damning evidence — even if the reporter is his protege. McLeary survives and there is poetic justice in the possibility that Chapman’s sordid misdeeds would make front page headlines in the scandal sheet he created. The lesson here is beware of the monster that you create — most likely you’ll end up its victim.