|

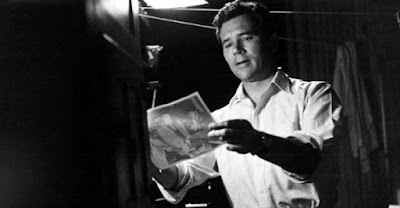

| Allen Baron, “Blast of Silence” (1961). Noir for the year's last day. |

Was that a popping cork or the report of a firearm?

By Paul Parcellin

Why is it that a lot of noirs take place around Christmas, but not so many focus on New Year’s Eve? Granted, New Year’s doesn’t carry the same weight as Christmas — it’s just not a family holiday, with all of the sentimental memories (or emotional baggage) that you may find in Yuletide festivities.

But starting a new year can bring more than a wisp of heartfelt reflection, sometimes quite unexpectedly. Anticipation of a fresh start mixed with pangs of regret about the year gone by often make it a bittersweet occasion. It marks the end of the holiday season and is among the early days of the winter ahead.

Like an abbreviated Mardi Gras, it allows us one night to party before facing the grayness of the coming season.

In the noir universe a new start can mean different things — unsavory things. In noir, a new start often means the beginning of the end. Noir new starts take time to develop and blossom while endings are often abrupt and unmerciful.

Here are some noirs (and other kinds of crime stories) with a New Year’s theme. They may not all include party hats and streamers, but in each the new year is more to be feared than welcomed:

|

| Sue Moore, William Powell, Jack Adair, “After the Thin Man.” |

“After The Thin Man” (1936)

OK, so it’s not a noir, more like a murder mystery wrapped in a screwball comedy. But it’s got a lot of noir atmosphere, fedoras, double breasted suits and femmes fatale in furs. Plus it’s based on the writings of Dashiell Hammett. A goodly chunk of the film does indeed take place on the eve and day of the new year, a fitting holiday for a Thin Man mystery. It’s also a comfortable setting for the story’s hero, Nick Charles, who approaches life as if it’s one long cocktail party. It’s the second boozy installment in a series of six Thin Man movies made between 1934 and 1947. Popular for the fizzy chemistry between Nick and wife Nora, the couple inevitably becomes embroiled in criminal cases despite Nick’s insistence that he’s retired from the private detective biz.

As bleary eyed as the famous sleuth may be — he seems to be the toast of whichever town he happens to be in, here, it’s San Francisco — he’s the one who figures out the complex ins and outs of a mysterious murder and brings the perp to justice.

Don’t go looking for any symbolic meanings in this New Year’s romp. Instead, do something more useful, like searching for some gin, a bucket of ice and a cocktail shaker.

|

| Edmond O’Brien, Viveca Lindfors, “Backfire.” |

“Backfire” (1950)

When you land in a military hospital with spine injuries, as did World War II vet Bob Corey, you hope that the worst is behind you and normalcy will return. Not so, for Bob. He’s been planning to go into business with a military buddy— they’re going to become ranchers. But things begin to take an odd turn on Christmas Eve, when Bob is awakened by a strange woman with some unsettling news. But was it just a dream? He’s released from the hospital on New Year’s Day, and morning gets off to a horrifyingly bad start. It seems his would-be business partner has gotten himself into trouble and is nowhere to be seen. The police want information, but Bob has none to offer, except for that spooky visit from the lady in the middle of the night — and no one’s buying that.

|

| Allen Baron, "Blast of Silence," |

“Blast of Silence” (1961)

It’s a drag to have to work over the holidays. Still, hitman Frankie Bono is on the job and taking care of business. An overly ambitious Mafioso is getting coal in his stocking, so to speak, and Frankie is playing the role of bad Santa. But things get complicated. Frankie meets a girl and his outlook on life begins to change. He calls his employers to tell them that he wants to quit the job. It does not go over well, and they give him until New Year's Eve to perform the hit. There’s precious little joyful revelry here. The waning days of the year grow bleak for Frankie. He’s desperate and struggling to change his ways and make a fresh start. “Blast of Silence” is less about fresh starts and more a meditation on loneliness, and Frankie is in what must be the loneliest profession known to mankind, save for the Maytag repairman.

|

| Edward G. Robinson, “Little Caesar.” |

“Little Caesar” (1931)

New Year’s Eve marks a turning point in the career of Caesar Enrico Bandello, a small time hoodlum with an insatiable thirst for power. He organizes a nightclub holdup as patrons ring in the new year. While he and his gang make their exit, the small, paunchy criminal kills the city’s crime commissioner who happens to be a guest at the club. For Bandello, it’s both the start of his meteoric rise in the mob and the beginning of the end for him. As high as he rises in the organization he’s unable to wash the blood off his hands. From that day forward he’s a marked man and doomed to fail. Some viewers compare him with captains of industry who resort to any means necessary to ensure their advancement. In fact, Bandello’s rise from the gutter to prosperity is the stuff of the American dream — but an extremely skewed version of it.

|

| Frank Sinatra, Peter Lawford, Richard Conte, “Ocean's Eleven.” |

“Ocean’s Eleven” (1960)

Because it’s a heist movie set on New Year’s Eve, this one makes the list. The Rat Pack, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford, play veterans who served together in World War II and are set to knock off a Las Vegas casino. They mean to handle the heist with the precision of the military operations on which they were once deployed as a team. On the plus side, the movie begins with the always delightful Saul Bass (“Psycho,” “Vertigo,” “The Big Knife”) animated opening titles, which set the film’s bouncy mood. Beyond that, it’s all about Sinatra and company simply playing their affable selves — what else could they do? Richard Conte and Angie Dickinson round out the cast. As you might expect, no one seems to be taking it all so seriously, and neither should we.

|

| Louis Hayward, Joan Leslie, “Repeat Performance.” |

“Repeat Performance” (1947)

This is a story about do-overs, and in this case, a really big do-over. Talk about getting off on the wrong foot, Sheila Page kills her husband on New Year’s Eve, then gets her wish to redo the entire year. The seeds for this deadly event were planted in the previous months. So logically, if you can change the events leading up to the unfortunate circumstances things will change and hubby will be saved. Murder averted. No stripes, numbers or noose. But the question is whether or not certain events are in the stars or avoidable. In this case, circumstances leading up to the big event change, but fate has a curious way of grabbing hold of the wheel and taking us all on a wild ride. This may be the ultimate New Year’s Eve noir because we get not one, but two nights of celebration taking place a year apart. That’s nothing for Sheila to get excited about. As celebrations go, both are memorable, but that’s not necessarily a good thing.

|

| Gloria Swanson, William Holden, “Sunset Boulevard.” |

“Sunset Boulevard” (1950)

Who can forget the cringe-worthy New Year’s Eve celebration that Norma Desmond cooks up for Joe Gillis? He’s expecting a gala event, but Norma has planned a champagne toast for him and herself alone, followed by tangoing for two. Her sprawling, decrepit mansion, a monument to decadent Hollywood, is the fortress in which the once-famous silent screen star has hunkered down, refusing to see that the parade passed her by decades ago. It’s all too much for Gillis, a screenwriter whose sputtering career and naive outlook brought him to Norma’s door in the first place. Since then, he’s been a kept man. But as the new year dawns he finally sees Norma’s smothering embrace for what it is, and he bolts. But if he thinks he’ll get away from her that easily, he’s mistaken. Norma is the one who gets to write the third act.

|

| Joseph Cotten, Alida Valli, “Walk Softly, Stranger.” |

“Walk Softly, Stranger” (1950)

An amorous relationship blooms between a socialite and a crook in a film that’s part romantic drama, part film noir. Joseph Cotten is the gambler and con man who maneuvers his way into a comfortable position in an Ohio town. An unlikely romance between Cotten’s criminally motivated grifter and his boss’s daughter finally takes root on New Year’s Eve. It’s the story’s high point and the con man’s fortunes begin a steady decline from that evening on. This is a story about the redemptive powers of love, a theme atypical of noir. In fact, you might say it’s an anti-noir point of view. But when you’re drawing lines between what’s noir and what isn’t, consider that there are degrees of noir, despite what purists insist. It’s not an all or nothing proposition, and “Walk Softly, Stranger” has the necessary ingredients that allow it to fit snugly within the noir canon.