|

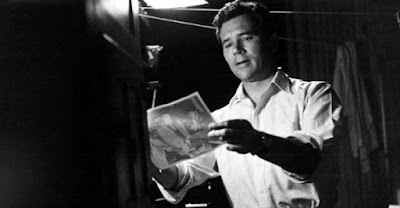

| Humphrey Bogart, Gloria Grahame, ‘In a Lonely Place’ (1950). |

By Paul Parcellin

You’ve probably heard that screenwriters get little respect in the big town, and by many accounts that’s true. They labor in isolation, punching out fresh ideas, pouring their deepest emotions onto their pages only to have their hearts broken.

Their masterpieces are rewritten by faceless studio hacks who turn them into pale shadows of what they were.

Or at least, that’s how screenwriters tell it.

Samuel Goldwyn used to call his writers schmucks with typewriters. When he wanted refurbished versions of recent hits he’d tell them, “Give me the same thing, only different.”

Writers were, and still are, famously powerless in the picture biz. They’re one of the most essential and least appreciated cogs in the movie making machine.

Each of the four movies below offers a powerful and fairly unvarnished view of the rough treatment the Hollywood studio system could dish out, and no doubt still can.

The writers behind these films, the ones who actually pounded out the pages, not the ones on screen, obviously took glee in mauling the Hollywood establishment. They draw blood. It’s fun to watch:

|

| Bogart and Grahame, 'In a Lonely Place.' |

‘In a Lonely Place’ (1950)

Director Nicholas Ray channels the Dorothy B. Hughes novel, starring Humphrey Bogart as Hollywood scribbler Dixon Steele, a tightly wound script jockey in a creative slump. Steele loathes the studio system and the egotistical no-minds who seem to thrive in it.

One evening Steele hosts a young woman at his apartment whom he tasks with summarizing a novel for him, a piece of drivel the studio wants him to adapt. And why not? She thinks the book is swell, and Steele can’t bear to waste time poring over the dreck. The next day the girl turns up dead and Steele is a suspect. He was one of the last to see her alive, and it’s well known that he’s an angry and violent bugger.

He meets Laurel Grey (Gloria Grahame), a neighbor who provides him with an alibi that keeps him out of the pokey for that murder rap, for the time being at least. A romance between them blossoms, but under these circumstances how long will it be until it dies on the vine?

This was the first film to roll off the production line of Bogart’s independent company, Santana Pictures Corporation, and with its downbeat ending the public stayed away. A pity. Bogart thought it was a failure. How wrong he was.

|

| Gloria Swanson, William Holden, 'Sunset Boulevard.' |

‘Sunset Boulevard’ (1950)

The same year that Bogart’s Dixon Steele dodged police investigators, screenwriter Joe Gillis (William Holden) has the opposite problem. He can’t get arrested in this town (L.A.). Producers aren’t interested in his latest stuff, a rehash of something that wasn’t very good to begin with. Worse still, repo men are after his car, and in Los Angeles losing your car is like getting your legs cut off.

He blunders into the crumbling estate of former silent screen siren Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) and talks his way into rewriting a putrid script the lady penned. It’ll be a vehicle for her return to Hollywood immortality, she thinks.

Gillis has a couple of B-pictures to his credit and is just about washed up in his short, anemic screen career. But he sees this odd turn of events as an opportunity to stay afloat financially for a while. Gillis thinks Norma is a soft touch, but it turns out she’s a lot more than the poor sap bargained for.

The delusional prima donna browbeats hapless Gillis into becoming her full-time bunk mate, and it slowly dawns on him he ain’t the one pulling the strings in this puppet show.

Norma finally gets the closeup she’s been craving, but not before Gillis takes an unscheduled dip in her swimming pool, a few bullet holes pumped into his torso. Turns out, the writing game is tougher than it looks.

|

| John Turturro, Jon Polito, 'Barton Fink.' |

‘Barton Fink’ (1991)

Broadway playwright Barton Fink (John Turturro) wants to create a new kind of theater, one aimed at “the common man.” Or so he thinks.

His new hit, about regular folks, is the toast of the Great White Way. Trouble is, his patrons are the kinds of monied twits he despises.

Fink, a thinly veiled caricature of socially aware playwright and screenwriter Clifford Odets, answers the call to come write for the pictures in Hollywood. It’s against every fiber of his bohemian being, but he rationalizes that he’ll pocket enough moolah to write scores more socially relevant plays.

Set in the early 1940s, the dawn of American film noir, Fink arrives in Los Angeles like a fish rocketed out of its aquarium and plopped into the middle of the desert. He meets a gaggle of characters who disappoint and frighten him, much like the New York contingent did.

There’s the blowhard, pushy studio chief (Michael Lerner), the respected author who’s churning out tripe for the movie mill (John Mahoney), and back-slapping, rotund insurance salesman Charlie Meadows (John Goodman) who is staying next door to Fink at a gothic horror show of a hotel in downtown Los Angeles.

Assigned to write a wrestling picture, Fink’s adventure in the screen trade soon goes horribly wrong. He becomes enmeshed in a genuine noir nightmare — fitting for this time and location.

Did I mention that this is a Coen brothers' film? The surreal irony, their trademark, bleeds off of the screen as we witness Fink’s descent into the netherworld. They don’t call this town “Hell A” for nothing.

|

| Tim Robbins, Vincent D'Onofrio, 'The Player.' |

‘The Player’ (1992)

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Robert Altman’s poisonous valentine to Hollywood, which came out at the peak of spec script fever.

Studio executive Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) is receiving threatening mail from an anonymous screenwriter who claims Mill snubbed him. The movie exec is rattled and tries to track down the one who’s sending him the nasty stuff. The problem is, out of the dozens of writers he’s ghosted, which one is harassing him?

Mill’s investigation leads to screenwriter David Kahane (Vincent D’Onofrio), who certainly does despise Mill, but is he the one threatening to do away with him? Mill’s luck keeps getting worse. The buzz around town is that a new executive at the studio, Larry Levy (Peter Gallagher), is going push Mill out.

Meanwhile, the cops show up and start asking the beset executive some difficult questions about himself and Kahane. And things don’t end up so good for Kahane, either.

As the song says, “There’s no business like show business,” and that’s probably a good thing.

Believe it or not, Jan. 5 is National Screenwriters Day. Its purpose is to honor the writers behind the stories, dialogue and characters in films and TV. You might consider taking a screenwriter to lunch on that day. He or she could probably use some nourishment and a shoulder to cry on.